Fountain of Sorrow

The Deplorable Fate of Kissengen Springs

About ten years ago I wrote a song that came from a place within me of deep sorrow inflamed by a sense of resentment. The song tells of an historic event in the history of Florida – the complete and utter demise of a natural flowing spring outside the town of Bartow, the county seat of Polk County. Although today many of Florida’s natural flowing springs are showing signs of pollution, their crystalline waters are still nothing short of iconic. And to some… sacred. Many of the springs were deemed healing by native people prior to Columbus and the early explorers and conquistadors from Spain. Such a flowing spring existed in Polk County in the basin of the Peace River. It was called DeLeon Springs in the old days – alluding, I suppose, to Ponce DeLeon, a Spanish explorer who was seeking a legendary “fountain of youth.”

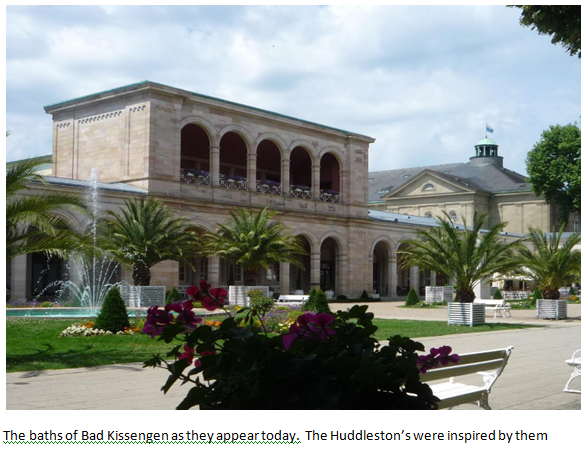

It was not only the native people who deemed the clear cold waters to have therapeutic powers. In 1883 the springs were bought and owned by some medical doctors named Huddleston. They had visions of turning the springs into a rehabilitation facility modeled after the spas and baths of Germany. The name “Kissengen Springs” refers to the “baths” of Bad Kissengen in Bavaria, Germany, of which the Huddleston’s were aware.

Needless to say the development of Kissengen Springs outside Bartow never quite rose to the grandeur of their Bavarian namesake. Nevertheless, the springs became an unparalleled natural attraction to the people of southern Polk County and beyond.

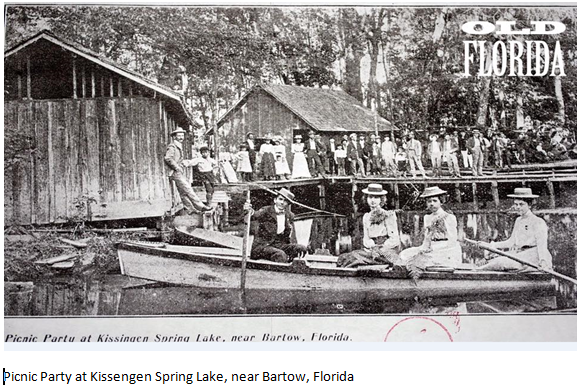

“When you think about summertime fun, what runs through your mind? A day at the beach? A picnic in the park? Dancing the night away? For some long-time residents of Polk County, it was all three and then some at a little place back in the woods between Bartow and Homeland called Kissengen Spring.” S.L. Frisbie, Publisher “Polk County Democrat”

Having been reared in Lakeland, about 10 miles west of Bartow, and having a dad whose religion, you might say, was nature, I experienced the wondrous effects of many of the cold flowing springs of Florida first hand, including Kissengen. Unfortunately Kissengen Springs which produced more than 20 million gallons of crystal clear cold water per day stopped flowing entirely in February 1950. The reason for this is memorialized on a delicately worded historical plaque at a former phosphate strip mine location now called “Mosaic Peace River Park:” “The spring ceased to be a tourist destination after the groundwater was captured for other uses.” (italics added)

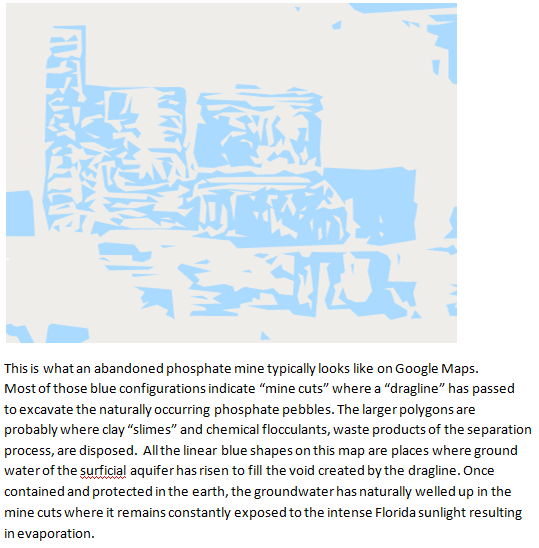

Mosaic is world’s largest producer of phosphate fertilizers for agriculture. Founded in 2005 Mosaic represents the final consolidation of a panoply of smaller strip mining and fertilizer production companies that span more than a century in west central Florida – sometimes euphemistically called “Bone Valley.” It occupies an area of over 800 square miles. Anyone who has a computer and an internet connection can see the wide-spread decimation of the natural environment the phosphate mining industry has wrought on that part of Florida.

Cogongrass is an Asian grass considered to be one of the world’s most pernicious weeds. It particularly likes the degraded soils of old phosphate mines

I was recently introduced to Oscar Corral, a film producer working on a documentary based on the current endangerment of Florida springs – due mainly to non-point-specific pollution that comes with unlimited residential and urban development. He was aware of the loss of Kissengen Springs and proposed that I meet his videographer at the former site of the springhead and perform my song. Since I wrote the song with the intention of telling the story of Kissengen Springs to as many as possible, I jumped at the chance to have it included in Oscar’s film. So, on a hot day in June, with the temperature hovering above 95F, I made arrangements with the videographer to meet near Mosaic Park where, based on satellite images, we reckoned we would find what’s left of Kissengen Springs.

Actually the former springs is not located within the park boundaries, but rather is found on the edge of a large conservation area on that stretch of the Peace River owned by Trustees of the Internal Improvement Trust Fund (TIITF) – the governor and is cabinet, and managed by FDEP. We determined the remains of the springs are most easily accessible from a cattle gate on highway US 17, well north of the park entrance. This is the property of Clear Springs Land Company – dedicated to developing formerly mined phosphate lands for cattle ranching and berry production. They own 18,000 acres. Apparently the site is also designated an archeological site and ordinary people aren’t really encouraged to go there. However, there is legal access via the Peace River.

The gate was locked, so after crossing a railroad track we had to traverse it by hefting our bicycles, camera equipment and guitar over the top which landed us in a cattle pasture. At least it was the approximation of a cattle pasture since the only pasturage in sight was dominated by one of the world’s most pernicious weeds, called cogongrass (imperata cylindrica). Cogangrass was first introduced to Florida for cattle forage and soil stabilization. Then, unfortunately, it was discovered that the grass was unsuitable for both of those purposes. Its virulent pace of reproduction, its resistance to any form of control or eradication, its ability to negatively affect soil chemistry and its poor nutrient value as cattle fodder account for its undesirability, but due to the lack of any organized and effective efforts to control it, cogongrass is rapidly spreading throughout the state of Florida. It particularly likes the degraded soils that characterize and dominate old phosphate mines.

Cogangrass was first introduced to Florida for cattle forage and soil stabilization. Then, unfortunately, it was discovered that the grass was unsuitable for both of those purposes.

As we peddled down a rough two-track trail through a few muddy pastures I noticed that in addition to the cogongrass other invasive exotics were thriving there – namely Brazilian Pepper (Schinus terebinthifolius) and Camphor trees (Cinnamomum camphora). Both these plants are on the Category 1 list of invasive species compiled by the Florida Exotic Pest Plant Council. The plants on this list are characterized by their documented ecological damage caused by displacing native species, changing community structures, ecological functions and hybridizing with native plants.

Finally, after about a mile, the land began to slope away to our right (south), so we parked our bikes and took to foot. We crossed another gate and found ourselves in a shady area with significant bodies of water on both sides of the road barely visible through the underbrush. From what we could see I surmised we were looking down at abandoned phosphate pits. Their steeply sloping banks and complete absence of a littoral zone, not to mention the almost iridescent blue-green tones of the algae-laden water, were a dead giveaway. According to the map the body of water to our left was actually joined to the Peace River, although it seems unlikely, given the extensive alteration of the surrounding landscape left by the strip mining operations, that it was a natural channel.

The last leg of our trip led us between more overgrown phosphate pits to the edge of a little woods. There we easily crossed another fence that had already been trampled by cattle. We picked our way through some shallow muddy sloughs and finally came across what had once been the source of legendary joy and wonder – the deplorable remains of Kissengen Springs.

Brazilian Pepper is on the Category 1 list of invasive species compiled by the Florida Exotic Pest Plant Council.

The remains of a huge cypress tree lie among its spindly successors near what’s left of a Polk County landmark… Kissengen Springs. 95F in the shade that day.

There were two shallow muddy depressions not much different than the cattle watering holes you often see in these parts. In the first one we found a catfish in its death throes in the eutrophic stagnant water. There appeared to be a flow of water entering the pond at the far end where a little stream all but disappeared in the tall aquatic grass. I tested the flowing water and it was warm and clear which indicated to me that it was surface water. I can only imagine that it was seeping back into the ground as quickly as it flowed in; perhaps through the original vent where the springs once welled up, but that day the water entrapped there was far too scummy and algal to see any detail below the surface.

Apparently in the days when the springs were still naturally functional there was a berm around the springhead and a spillway where the water flowed down a sluice down to the Peace River. I recalled reading a report that a differential in ground water pressure in the upper Peace River had over the years actually caused the flow of water to reverse directions. I wondered whether that little stream of water where the water was flowing into the pool was at one time the run that channeled the spring water into the Peace River, but the tall dense grass that shrouded that little stream was a little too intimidating to make it worth exploring further.

One of two pools of what appears to be stagnant water that mark the site of the legendary Kissengen Springs. Water flows in but does not appear to alter the quantity or quality in the pool.

It is said and verified in photographs that there was once a dance pavillion with a big Wurlitzer juke box, a snack bar, changing rooms, and a pier built on one side of the spring. The only remains of any structure I saw there were a set of concrete steps at one side of the shallow depression that went nowhere. In an adjacent depression there was more stagnant water and a huge oak tree that had collapsed. It was there that the videographer, a splendid young fellow, chose to film me singing my song.

I cannot say that I did not experience some irony singing a protest song in a deserted and isolated location where only a handful of the most driven explorers would ever venture, but on the other hand I had to bear in mind that this was only a segment of a much larger production, and that hopefully it would make sense in its final context.

He asked me how it made me feel, and I could hardly find the words to express it. The only thing I could compare it to would be that creepy sensation you might have if you were visiting an extermination camp, or the site of a brutal massacre, like Babi Yar or Katyn Forest, where something truly genocidal had taken place not so long ago, and there were still hungry ghosts lurking around.

Although I didn’t try to express it at that time, I felt a simmering anger that… not only had a place of extraordinary natural beauty been rendered unbelievably ugly, it had been a place that also inspired joy and delight, wonder and fascination (like beholding the infinity of the vast starry firmament). I could imagine based on my own youthful experiences what it was like for those simple happy people of Bartow and neighboring communities to come to this haven in the woods to bathe and mingle and experience the luxury of immersion in the seemingly endless abundance of cold clear water, to stand atop the diving tower and look down directly into the glassy boil that seemed to well up from the very heart of the earth. People did that for generations, and suddenly it was all gone, as though awakening from a pleasant dream.

No one person is responsible for the loss of Kissengen Springs, but all signs point to the culpability of an industry and a kind of mass hypnosis that not only allowed the destruction of the springs, but has never held the perpetrators accountable for what happened. On the contrary they accepted their blood money. It’s obvious, isn’t it? When you walk through miles of useless degraded land, overgrown with invasive vegetation where there are still old cast-off rusty pipes and wires strewn around and huge mine pits gouging the earth a stone’s throw from where the springs once prospered, it’s obvious what happened to the springs. Yet just down the road, there lies “Mosaic Peace River Park” with its historical brass plaque that says, “The spring ceased to be a tourist destination after the groundwater was captured for other uses.” The historical society obviously dared not utter the word “phosphate” since it was the mother of all phosphate mines and fertilizer production that donated the land to the public. The industry mined it and effectively destroyed the natural order that had prevailed there since the dawn of time, and then returned it to the public as a gift, and people bowed their heads and expressed their gratitude.

Dennis Mader for 3PR News

Here is a link to Ode to Kissengen Springs, the song referenced in the article above. This version was recorded in the studio at WMNF in Tampa September 17, 2016. The video includes a rather long-winded interview with the host, Pat Gallagher. The actually music begins at 2:40….