Phosphate giant Mosaic agrees to pay nearly $2 billion over mishandling of hazardous waste

· Craig Pittman, Tampa Bay Times Staff Writer

Thursday, October 1, 2015 12:53pm

Mosaic Fertilizer, the world’s largest phosphate mining company, has agreed to pay nearly $2 billion to settle a federal lawsuit over hazardous waste and to clean up its operations at six Florida sites and two in Louisiana, the Environmental Protection Agency announced Thursday.

“The 60 billion pounds of hazardous waste addressed in this case is the largest amount ever covered by a federal or state … settlement and will ensure that wastewater at Mosaic’s facilities is properly managed and does not pose a threat to groundwater resources,” the EPA said.

The EPA had accused Mosaic of improper storage and disposal of waste from the production of phosphoric and sulfuric acids, key components of fertilizers, at Mosaic’s facilities in Bartow, New Wales, Mulberry, Riverview, South Pierce and Green Bay in Florida, as well as two sites in Louisiana.

The EPA said it had discovered Mosaic employees were mixing highly-corrosive substances from its fertilizer operations with the solid waste and wastewater from mineral processing, in violation of federal and state hazardous waste laws.

“This case is a major victory for clean water, public health and communities across Florida and Louisiana,” said Cynthia Giles, assistant administrator for EPA’s Office of Enforcement and Compliance Assurance.

Mosaic CEO Joc O’Rourke said the company is “pleased to be bringing this matter to a close” and pledging to be a good environmental steward. The Minnesota-based company was formed in 2004 by a merger of IMC Global with the crop nutrition division of Cargill.

Mosaic officials in Florida said the EPA investigation and negotiations for a settlement have been going on for eight years, and what they were doing was something everyone in the phosphate industry was doing as well.

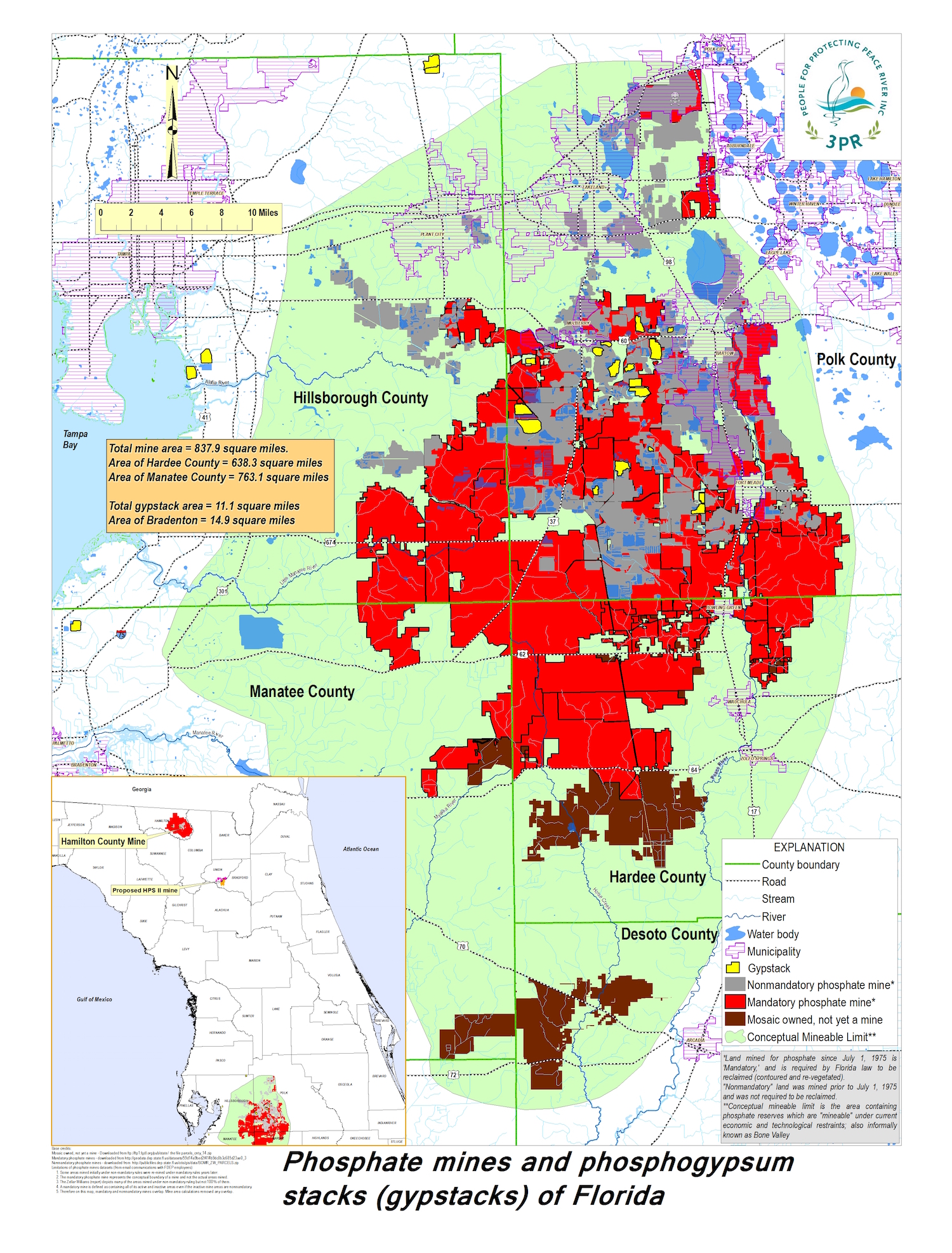

The settlement with the EPA, the Justice Department, the Florida Department of Environmental Protection and the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality will have no impact on Mosaic’s continued employment or on its future mining expansion plans in DeSoto, Hardee and Manatee counties, they said.

First discovered by an Army Corps of Engineers captain in 1881, Florida’s phosphate deposits today form the basis of an $85-billion industry that supplies three-fourths of the phosphate used in the United States. Although phosphate mining provides a major financial boon to the small communities in which the mines are located, it also leaves behind a major environmental mess.

The miners use a dragline with a bucket the size of a truck to scoop up the top 30 feet of earth and dump it to the side of the mine. Then the dragline scoops out the underlying section of earth, which contains phosphate rocks mixed with clay and sand.

The bucket dumps this in a pit where high-pressure water guns create a slurry that can then be pumped to a plant up to 10 miles away.

At the plant, the phosphate is separated from the sand and clay. The clay slurry is pumped to a settling pond, and the phosphate is sent to a chemical processing plant where it is processed for use in fertilizer and other products. The sand is sent back to the mine site to fill in the hole after all the phosphate is dug out.

A byproduct, called phosphogypsum, is slightly radioactive so it cannot be disposed of easily. The only thing the miners can do with it is stack it into mountainous piles next to the plant. Florida is such a flat state that the 150-foot-tall “gyp stacks” are usually the highest point in the landscape for miles around. They contain large pools of highly acidic wastewater on top, too.

“Mining and mineral processing facilities generate more toxic and hazardous waste than any other industrial sector,” Giles said. “Reducing environmental impacts from large fertilizer manufacturers operations is a national priority for EPA.”

Mosaic’s production of pollution is so great that in 2012, the Southwest Florida Water Management District granted the company a permit to pump up to 70 million gallons of water a day out of the ground for the next 20 years. Mosaic is using some of that water to dilute the pollution it dumps into area creeks and streams so it won’t violate state regulations.

The EPA investigation was prompted by a 2003 incident in which the Piney Point phosphate plant, near the southern end of the Sunshine Skyway, leaked some of waste from atop its gyp stack into the edge of Tampa Bay after its owners walked away.

That prompted EPA to launch a national review of phosphate mining facilities, said EPA spokeswoman Julia Valentine. That’s how inspectors found workers were mixing the corrosive substances from the fertilizer operations with the phosphogypsum and wastewater from the mineral processing, she said.

That mixing was something everyone in the industry did, according to Richard Ghent of Mosaic’s Florida operations. The EPA said that violated both state and federal law and put groundwater at risk. It has previously gotten settlements from two other companies, one of which, CF Industries, has since been taken over by Mosaic.

Despite the mishandling of the waste, Debra Waters, Mosaic’s director of environmental regulatory affairs in Florida, said the company has seen no change in the area’s groundwater as a result, which EPA officials said was correct.

The fact that the negotiations have been going on for so many years, she said, “should indicate that there’s no imminent threat.”

The company will invest at least $170 million at its fertilizer manufacturing facilities to keep those substances separate from now on. Mosaic will also put money aside for the safe future closure of the gypsum stacks using a $630 million trust fund it is creating under the settlement. That money will be invested until it reaches $1.8 billion, which will pay for the closures.

The South Pierce and Green Bay plants, both in Polk County, are already in the process of shutting down, with the closure of the gyp stacks already underway, Waters said.

Mosaic will also pay a $5 million civil penalty to the federal government, a $1.55 million penalty to the State of Louisiana and $1.45 million to Florida, and it will be required to spend $2.2 million on local environmental projects to make up for what it has done.

Mosaic, which runs television ads touting its importance in growing crops to feed the world, has previously run afoul of the EPA on its air pollution standards. However, last year company was rated one of the top 50 employers in America based on salary and job satisfaction. Mosaic employs about 1,200 people in Hillsborough County alone.