Author: 3pranna

Polk County mined land…what to do with it?

After mining, it will be the county that tries to figure out what in the heck they will do with their thousands of acres of mined lands. Health studies would be required to assess the toxicity and possible radiation threats left behind by the upheaval of formerly native systems. Is this what Hardee, Desoto and Manatee county can look forward to?

Continue reading “Polk County mined land…what to do with it?”

Mosaic slapped with $2 Billion clean up settlement Oct. 2015

Phosphate giant Mosaic agrees to pay nearly $2 billion over mishandling of hazardous waste

· Craig Pittman, Tampa Bay Times Staff Writer

Thursday, October 1, 2015 12:53pm

Mosaic Fertilizer, the world’s largest phosphate mining company, has agreed to pay nearly $2 billion to settle a federal lawsuit over hazardous waste and to clean up its operations at six Florida sites and two in Louisiana, the Environmental Protection Agency announced Thursday.

“The 60 billion pounds of hazardous waste addressed in this case is the largest amount ever covered by a federal or state … settlement and will ensure that wastewater at Mosaic’s facilities is properly managed and does not pose a threat to groundwater resources,” the EPA said.

The EPA had accused Mosaic of improper storage and disposal of waste from the production of phosphoric and sulfuric acids, key components of fertilizers, at Mosaic’s facilities in Bartow, New Wales, Mulberry, Riverview, South Pierce and Green Bay in Florida, as well as two sites in Louisiana.

The EPA said it had discovered Mosaic employees were mixing highly-corrosive substances from its fertilizer operations with the solid waste and wastewater from mineral processing, in violation of federal and state hazardous waste laws.

“This case is a major victory for clean water, public health and communities across Florida and Louisiana,” said Cynthia Giles, assistant administrator for EPA’s Office of Enforcement and Compliance Assurance.

Mosaic CEO Joc O’Rourke said the company is “pleased to be bringing this matter to a close” and pledging to be a good environmental steward. The Minnesota-based company was formed in 2004 by a merger of IMC Global with the crop nutrition division of Cargill.

Mosaic officials in Florida said the EPA investigation and negotiations for a settlement have been going on for eight years, and what they were doing was something everyone in the phosphate industry was doing as well.

The settlement with the EPA, the Justice Department, the Florida Department of Environmental Protection and the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality will have no impact on Mosaic’s continued employment or on its future mining expansion plans in DeSoto, Hardee and Manatee counties, they said.

First discovered by an Army Corps of Engineers captain in 1881, Florida’s phosphate deposits today form the basis of an $85-billion industry that supplies three-fourths of the phosphate used in the United States. Although phosphate mining provides a major financial boon to the small communities in which the mines are located, it also leaves behind a major environmental mess.

The miners use a dragline with a bucket the size of a truck to scoop up the top 30 feet of earth and dump it to the side of the mine. Then the dragline scoops out the underlying section of earth, which contains phosphate rocks mixed with clay and sand.

The bucket dumps this in a pit where high-pressure water guns create a slurry that can then be pumped to a plant up to 10 miles away.

At the plant, the phosphate is separated from the sand and clay. The clay slurry is pumped to a settling pond, and the phosphate is sent to a chemical processing plant where it is processed for use in fertilizer and other products. The sand is sent back to the mine site to fill in the hole after all the phosphate is dug out.

A byproduct, called phosphogypsum, is slightly radioactive so it cannot be disposed of easily. The only thing the miners can do with it is stack it into mountainous piles next to the plant. Florida is such a flat state that the 150-foot-tall “gyp stacks” are usually the highest point in the landscape for miles around. They contain large pools of highly acidic wastewater on top, too.

“Mining and mineral processing facilities generate more toxic and hazardous waste than any other industrial sector,” Giles said. “Reducing environmental impacts from large fertilizer manufacturers operations is a national priority for EPA.”

Mosaic’s production of pollution is so great that in 2012, the Southwest Florida Water Management District granted the company a permit to pump up to 70 million gallons of water a day out of the ground for the next 20 years. Mosaic is using some of that water to dilute the pollution it dumps into area creeks and streams so it won’t violate state regulations.

The EPA investigation was prompted by a 2003 incident in which the Piney Point phosphate plant, near the southern end of the Sunshine Skyway, leaked some of waste from atop its gyp stack into the edge of Tampa Bay after its owners walked away.

That prompted EPA to launch a national review of phosphate mining facilities, said EPA spokeswoman Julia Valentine. That’s how inspectors found workers were mixing the corrosive substances from the fertilizer operations with the phosphogypsum and wastewater from the mineral processing, she said.

That mixing was something everyone in the industry did, according to Richard Ghent of Mosaic’s Florida operations. The EPA said that violated both state and federal law and put groundwater at risk. It has previously gotten settlements from two other companies, one of which, CF Industries, has since been taken over by Mosaic.

Despite the mishandling of the waste, Debra Waters, Mosaic’s director of environmental regulatory affairs in Florida, said the company has seen no change in the area’s groundwater as a result, which EPA officials said was correct.

The fact that the negotiations have been going on for so many years, she said, “should indicate that there’s no imminent threat.”

The company will invest at least $170 million at its fertilizer manufacturing facilities to keep those substances separate from now on. Mosaic will also put money aside for the safe future closure of the gypsum stacks using a $630 million trust fund it is creating under the settlement. That money will be invested until it reaches $1.8 billion, which will pay for the closures.

The South Pierce and Green Bay plants, both in Polk County, are already in the process of shutting down, with the closure of the gyp stacks already underway, Waters said.

Mosaic will also pay a $5 million civil penalty to the federal government, a $1.55 million penalty to the State of Louisiana and $1.45 million to Florida, and it will be required to spend $2.2 million on local environmental projects to make up for what it has done.

Mosaic, which runs television ads touting its importance in growing crops to feed the world, has previously run afoul of the EPA on its air pollution standards. However, last year company was rated one of the top 50 employers in America based on salary and job satisfaction. Mosaic employs about 1,200 people in Hillsborough County alone.

Kissingen Spring

At one time the Historic Kissengen Spring discharged up to 20 million gallons of water a day into the Peace River. The spring’s pool was 200 feet in diameter and reached a depth of 17 feet above the spring vent.

Its boil reportedly was so powerful that the strongest swimmer could not reach it. Archaeological evidence shows this area of the Peace River was inhabited by Native Americans who established large villages near the river’s springs. In the late 1800s developers sought to acquire the spring as a resort destination and sanatorium. Although plans for rail lines, trolleys, and boats never were realized to exploit the spring for tourism, a dance floor, dive platform, and bathhouses were built, and thousands of locals and tourists visited over 75 years.

In the 1930s the popular spring was the site of major political rallies. During World War II, it served as a rest and recuperation resort for members of the military based near Bartow. The spring ceased to be a tourist destination after its groundwater was captured for other uses.

The spring vent was plugged in 1962, and it ceased to flow again. Read more here.

To learn more about the destruction of aquifers and running dry, read the USGS research here.

We Believe That

- The Peace River Heartland, a name for the area of central Florida which includes Hardee, DeSoto, Manatee and Charlotte Counties, has a unique, much varied, and valuable character. If this area is to be discovered by future generations, it must be preserved.

- The safety and well-being of the citizens of our area is more important than the profits of the phosphate industry.

- The preservation of native and agricultural lands is of great importance for our well-being, but even more, for the well-being of those who would live here in the future.

- Permanent alteration of our land is not corrected by reclamation or mitigation, as the soils and aquifers are so extremely rearranged.

- What goes into the ground here in the Peace and Myakka River watersheds can potentially end up in our wells or in Charlotte Harbor at the end of the stream.

- Industrial chemicals have no place in our soils with our near surface aquifers.

- We have a responsibility to all future generations to leave our natural environment as intact, rich and varied as we found it, if not better.

- Someone must care. This means that a value beyond money must prevail.

- That profit and preservation can coexist. This is Florida, a land of tourism, and we are part of it.

- The Peace River Heartland, known to the phosphate industry as “Bone Valley“, has a unique natural and agricultural character which has many superior alternatives to phosphate strip mining.

The Peace River Heartland

People for Protecting Peace River encourages all forms of outdoor activities, including recreational fishing and hiking because people need to have fun!

The Canoeing, Kayaking, and Outdoors Capital of Florida

The Hardee County Visioning Report mentioned “blue ways” as a good way to highlight the importance of the Peace River Heartland of Hardee, Desoto, Manatee and Charlotte Counties. In no way is a blue way more important than in providing drinking water, but we believe having the support of people who love the river for recreation is just as important.

People living and visiting on vacation love spending their day in their kayaks. As the you get to experience the Peace River outdoors related water sports, you’ll know why we see more new small business opening such as kayak shops, cafes, and more.

What the Future Holds for Mosaic’s “Bone Valley”

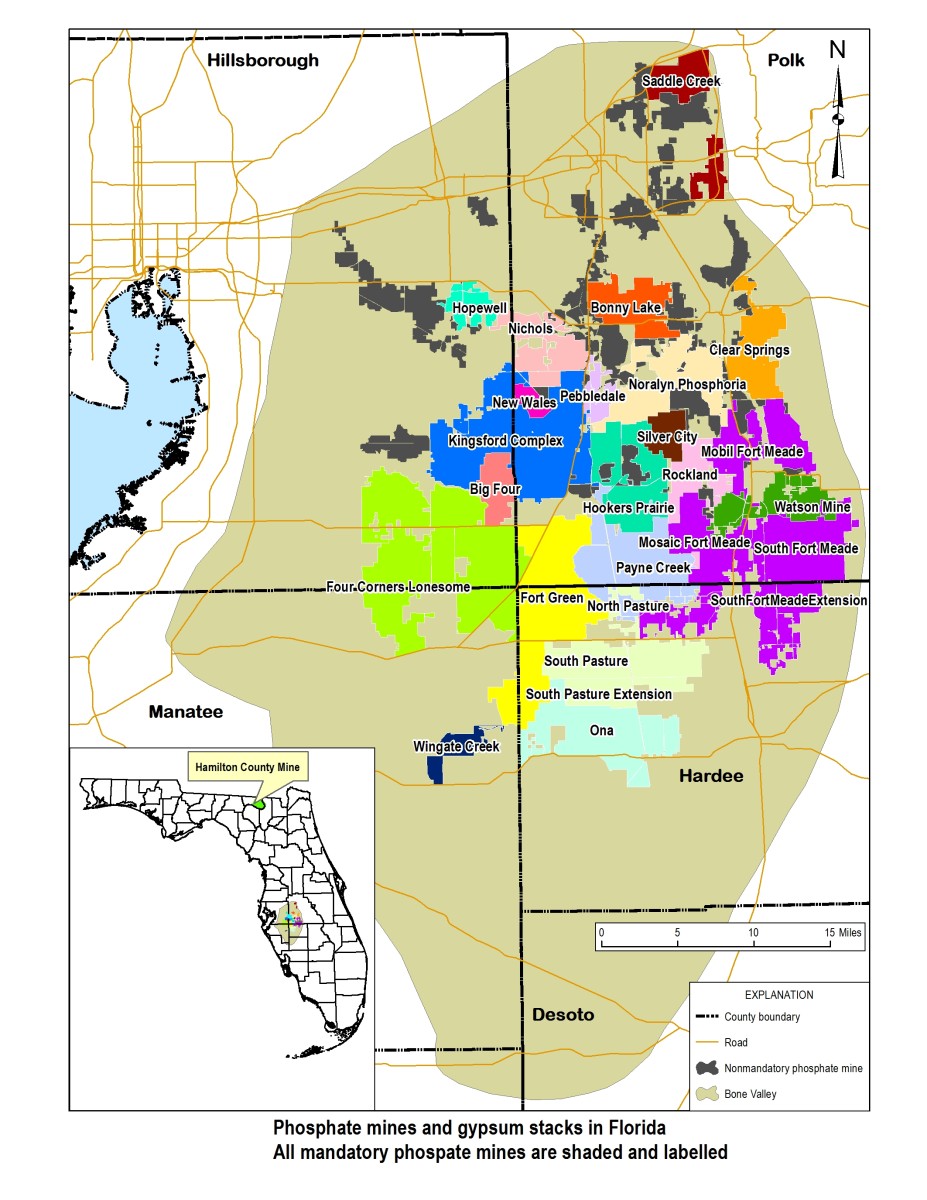

Mosaic’s “Bone Valley” in the Peace River Heartland

For the first time in history the entire Central Florida Phosphate Mining District is owned by one single company: Mosaic. They recently acquired CF Industries and their associated Ft Green/Hardee County mining and beneficiation operations – the South Pasture Mine Extension. Mosaic is presently seeking permits for an additional 52,000 acres of phosphate strip mining in Manatee, Hardee and DeSoto Counties.

These mines are the South Pasture Extension (7500 acres), Wingate East (3600), Ona (22,300) and DeSoto (18,300). The US Army Corps of Engineers Area-wide Environmental Impact Statement (AEIS) was meant to assess the direct and indirect as well as past, present and future consequences of so much phosphate strip mining. 3PR deemed the Final AEIS to be highly inadequate, inaccurate, antiquated and in many instances misleading with a pro-industry bias. Simultaneous with the initiation of the AEIS process Mosaic issued notices seeking US Army Corp Engineers 404 (Dredge and Fill Permits) for the four mines mentioned above.

If the permits are approved Mosaic will have carte blanche to pursue the same kind of environmentally disastrous surface mining operations that have blighted the eco-systems and watersheds of west central Florida for generations.

Fertilizer company negotiating possible Florida settlement costing more than $775 million

Matt Dixon, Naples News

5:04 PM, Dec 18, 2014

Federal and state environmental officials are negotiating in hopes of reaching a settlement with Mosaic, among the world’s largest fertilizer companies, over whether it “mishandled hazardous waste” at some of its Florida facilities.

The issue could ultimately cost the company hundreds-of-millions of dollars in facility upgrades and trust fund payments, in addition to a possible penalty of more than $1 million, according to state records and regulatory filings.

It’s part of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s crackdown on hazardous waste created by the mineral processing industry.

“The negotiations involving Mosaic are complex and ongoing,” said company spokesman Richard Ghent. “We are negotiating in good faith and we look forward to a successful resolution of the matter.”

Phosphate Ore is the mineral that companies mine and process when producing fertilizer. The toxic byproduct created by the process is stored in up to 200-foot tall piles known as “gypstacks,” which are called “mountains off hazardous waste” by some environmental groups.

“They can sometimes overflow and spill their toxic waste after strong storms or prolonged rain events,” the Sierra Club Florida wrote in a brochure about gypstacks.

The first settlement related to the EPA’s efforts was in 2010 between C.F. Industries, which operated a Plant City fertilizer plant, and the U.S. Department of Justice.

Under the settlement, the company agreed to spend $12 million to reduce the release of hazardous waste, and pay a $700,000 fine. In 2013, Mosaic spent $1.2 billion to buy CF Industry’s Central Florida-based phosphate business, which produce 1.8 million tons of phosphate fertilizer annually.

Orchids and Strip Mines Don’t Mix 2013

The phosphate mining company Mosaic is currently seeking permits that will allow them to mine more than 50,000 acres in Manatee, DeSoto and Hardee Counties. These mines will negatively affect the Peace River watershed water and Myakahatchee Creek which provide both Sarasota and North Port with drinking water, and encroach on Myakka State Park. Since Mosaic now owns exclusively all the phosphate reserves in west central Florida, people may wonder why you can scarcely turn on a radio or television these days without hearing or seeing their advertisements? Why do they blanket area newspapers with their reassurances and promises, with direct mailings and billboards extolling their virtues as trustworthy “stewards of the land,” planters of trees, and conservers of water resources? The answer is simple: Mosaic doesn’t need to sell its product in Florida since its main customers are huge fertilizer consortiums in Brazil, India and China. Here Mosaic needs only to sell its image and its brand. Continue reading “Orchids and Strip Mines Don’t Mix 2013”

Mosaic Closes Mine As Profits Plummet 70% Nov. 2013

Mosaic, one of Minnesota’s 10 largest public companies, said its revenue fell almost 30 percent last quarter; its stock, meanwhile, has dropped nearly 20 percent in 2013.

by Kevin Mahoney

November 5, 2013

The Mosaic Company said Tuesday that its third-quarter profit fell 70 percent and that it is closing one of its potash mines in Michigan.

The Plymouth-based potash and phosphate fertilizer provider announced that net earnings for the third quarter, which ended September 30, totaled $124.4 million, or $0.29 per share, down from $417.4 million, or $0.98 per share, during the same period in 2012. Earnings per share were $0.05 lower than what analysts polled by Thomson Reuters had expected.

Revenue, meanwhile, totaled $1.91 billion, down about 28 percent from $2.65 billion in the third quarter of 2012. Third-quarter revenue fell short of analysts’ projections of $1.97 billion.

Shares of Mosaic’s stock were trading down about 1.65 percent at $45.96 Tuesday afternoon, and they are down roughly 19 percent this year.

President and CEO Jim Prokopanko blamed the weak quarterly results on lower potash and phosphate prices, a late North American fall season, and cautious dealer behavior.

“We believe the current challenges in the environment in which we operate, for both phosphate and potash, are cyclical in nature and provide Mosaic opportunities to deploy capital, including shareholder distributions,” Prokopanko said in a statement. “The long-term outlook for Mosaic remains compelling.”

In addition to closing a mine in Michigan, the company said it would be exiting the “underperforming” Argentina and Chile distribution businesses, to focus more heavily on its growing business in Brazil.

Prokopanko said the company expects pricing to remain challenging going into 2014 and that international demand, especially in India and China, remains unpredictable.

Mosaic is among Minnesota’s 10 largest public companies based on revenue, which totaled $11.1 billion in its most recently completed fiscal year.